We got some time with Felix Reibl who, alongside fellow The Cat Empire bandmate Ollie McGill, has re-surfaced with a brand new and insanely powerful project called Spinifex Gum. With a lineup of iconic feature artists including Peter Garrett, Briggs and Emma Donovan, Spinifex Gum is the political and social push Australia has needed in the form of the power of music. We got to the bottom of what it is that plants Spinifex Gum as probably the most commanding and influential Australian album of 2017.

Do you remember the moment you thought, ‘OK I’m going to start this project and it’s going to be called Spinifex Gum’?

I first got to go to the Pilbara where a lot of these songs came from. Back in 2014 when I was asked to write a song for the Gondwana Indigenous Children’s choir and that group of people alone made me realise it was a special project I was going to be working on. I had no idea it would become an album or anything like that. Over many years of returning to the Pilbara, it slowly dawned on me that what we were making there was special and leading us as opposed to us leading it. A lot of albums you know what you’re working on in the beginning and you work under those constraints. Whereas this album involves a choir from Northern Queensland and there are these beats that we made of the area, we sampled sounds from within the mine area. So basketballs became bass drums, and we tuned trains. We found this way to style the production that interested Ollie and I a lot. Marliya of Gondwana Choir was such an inspiration in her knowledge of the area. The moment this idea occurred to me was when I first spent time with the choir in the Pilbara, I realised I was doing more than just writing a few songs for them. We were creating an album, and that album would have a sound and it would go on for many years to create something. It was a combination of those young voices in the choir and what the area itself revealed in terms of its sounds, atmosphere and it’s stories.

Was your first trip to Pilbara the first time you encountered/heard of Marliya?

Marliya is a Gondwana choir and Gondwana also run the choir called the Gondwana Indigenous Children’s Choir. I’ve gotten to known them over several years and I’ve worked with other Gondwana choirs before. Lyn Williams conducts and leads them. She is a person who I have enormous respect for and she has really high musical expectations for the children she works with. For starters with the choir they’re amazing characters but we really aim to set the bar high musically, we’re not imagining these people as teenagers, we’re imaging them as a professional outfit. We’re going to write music that is going to really challenge the expectations of the choir form. We’re going to expect so much of them that they are going to do better. *laughs* To answer your question I met them for the first time around 2014 but I have had contact with Gondwana Choir and I had known Lyn for a long time before.

Have you always had wanted to work with artists like Briggs, Marliya, Emma Donovan and Peter Garrett? Did you think of them as collaborators before putting the album together or was it an organic process?

I would say it came more on the organic side. At first I didn’t even know what I was creating and it was the sort of album that revealed itself to us. A few songs came first and we thought ‘Oh this is actually a really exciting sound’ and before we knew it we had about half an album of material featuring Marliya. We thought ‘What can we do to bring in the level of depth to the album?’, so I kind of aimed for the sky in a way. The songs became pretty political and then we were entering into a dialogue with a few of the songs. Then I started thinking ‘Well Briggs is one of the strongest voices in the Australian discussion on the indigenous disproportionate load of youth incarceration’. He’s been an advocate on that for a long time and he has an incredibly powerful voice. So I thought ‘We’ve got a song and we’ve got a choir of young people here, it’s sounding amazing, lets contact him.’ So I contacted Briggs and he agreed to be a part of it and that was a huge addition to it. As I was in the Pilbara, that Tom Waits song [Make It Rain] kept coming to me. A lot of the songs were about rainmaking or water and a famous land rights case around the building of the dam so I thought why don’t we translate the last verse of ‘Make It Rain’ to Yindjibarndi and get Em Donovan to sing it. Again, it happened really naturally. She loved the idea, we came up with the production for it. And it worked.

With Peter Garrett it was interesting because I thought as I’m in the area I’ve learnt a lot about the FIFO suicides as well as things like the Flying Foam Massacre which is an infamous event from colonial times. The song is about a troubled FIFO worker driving into the darkness and Peter is such an iconic Australian voice in that way. I thought of how special it would if he would play the voice of a suicidal FIFO worker driving at night. As soon as he was in the studio and sung it, it was as if it was meant to be. What I’m getting at is all of the guests on this album as well as the album itself happened in a natural way- we followed it as opposed to dictating it too early.

When you took this project and idea to them, how did they react? Or should I re-phrase, how excited were they?

Exactly. It’s not a usual proposition to ask someone to feature on this album. Usually you make an album and you say ‘Do you want to guest with me or feature on a song we made?’. In this case it’s like there’s a bit of explaining to do but it’s also a unique project. Marliya of Gondwana Choir is a teenage Aboriginal and Torres Straight group of young females who have exceptional ability. The songs come from Pilbara and are in a combination of Yindjibarndi and English and (you say) ‘do you want to be a part of that?’. It is not your usual pitch and it’s also political and mysterious in some cases. It’s just a very unique project and the guest artists were very interested artistically as well as from a social point of view.

In the song Malangungu featuring Peter Garrett and Marliya, the big bang at 2:30 is mind-blowing and powerful. Let me get into your mind with that.

That song started for me while I was driving at night time in the Pilbara at a crossing. Now all trains in the Pilbara take 2 and a half minutes to pass, they’re over 2kms long. You can imagine these dinging bells and this huge heavy mass driving in the darkness. And then there was this sense, after the red bells went out and after the boom gates lifted, there was immense darkness behind there and in the back of my mind there was a state of FIFO suicide in the area. FIFO being fly in fly out mine workers and at the same time I learnt about the Malangungu spirit which is a Yindjibarndi one. It says that it creeps people out but the spirit itself is afraid white people so if they want to go down to the river at night and they happen to have a white person, they’ll send down the white person first to scare off the spirit. The combination of those two things in that song, it’s a fairly esoteric connection. Learning about that spirit and hearing the news stories about the FIFO suicide made for the context of that song and the song is based in the mind and voice of a troubled FIFO worker. That was the best way I could begin that and then the iconic presence of Peter Garrett and his voice and just his atmosphere, really suited that character very well.

Also a part of that, I returned to the Yindjibarndi community 6 times over 3 and a half years and I’ve made good friends there. Every song that’s involved, a story or reference to a cultural spirit I’ve been in contact with that community and have permission to write about these things, so there’s been full transparency. It’s important to say that. There’s been a great effort not to appropriate but celebrate what I’ve been able to learn and have permission and encouragement to do that.

The music video for ‘Locked Up’ featuring Briggs was shot in a prison- a juvenile prison?

The location of that is the Old Pentridge Prison in Melbourne. Some girls from the choir flew down for that and it was a total freezing day to work in – they come from North Queensland. I suppose it’s a symbolic prison more than a functional one at the moment. With that song we wanted to make it just as politically direct as we possibly could. We wanted to make a point based around indigenous kids being disproportionately locked up in this country. The site for that clip works, we wanted to choose a prison.

You mentioned some of the girls from the choir were featured in the clip?

Some of them yeah. The choir is going to be 18 strong when we perform live, but we couldn’t fly all of them down, it’s an incredibly challenging prospect to get that choir around to locations everywhere. But there were about 7 or 8 of them that came down and we had a great time.

It’s a powerful clip – whose idea was that?

For that clip we worked with Briggs’ team. Briggs has a really close knit team around him that I respect. We worked with Josh and Heath, who’ve worked with Briggs on most of his clips. So in that case the direction came from their camp. We all agreed that we wanted it set in a prison.

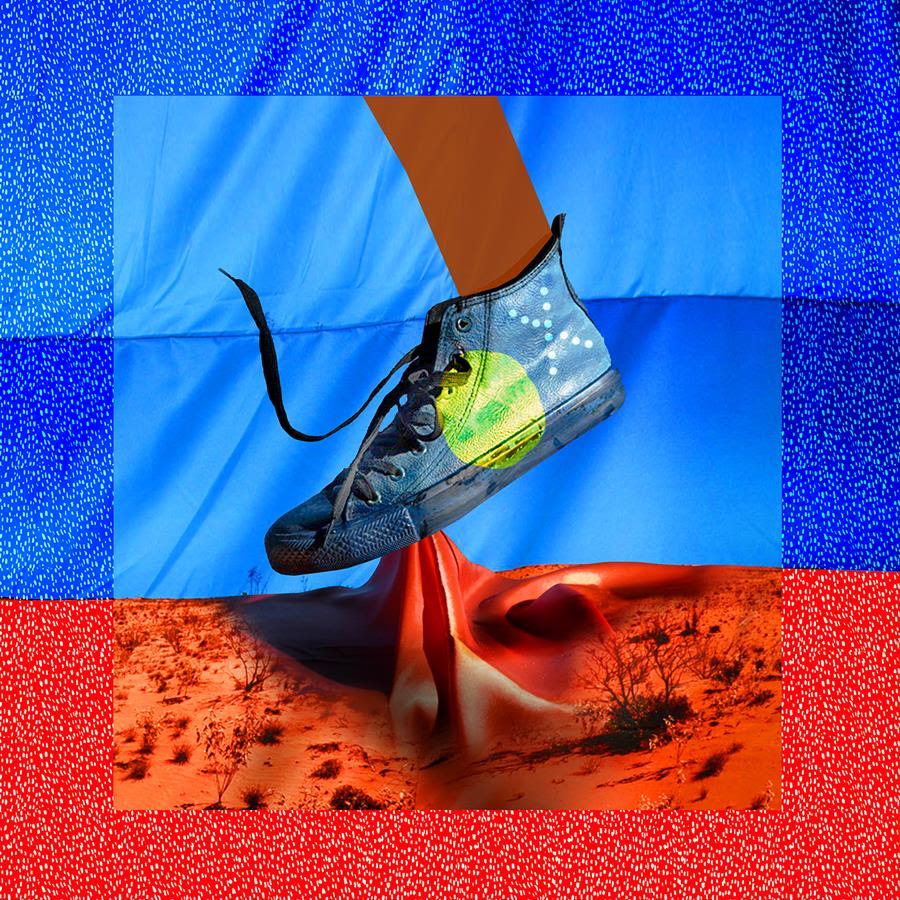

Tell me about the album cover.

The shoes that are featured throughout, all of those are painted by the girls of the choir. The landscape is that of the Pilbara. It plays on the idea of youth and drawing sound or something from the land itself. Aside from that we wanted to make it really colourful and striking when you looked at it. The base of the artwork is done by the young singers and we designed around it

This project and music has a very strong political stance and whoever listens to this will certainly be educated especially if they’re non-indigenous. How much does this message mean to you and how much does it mean that people understand what you’re trying to push with this?

This album is the most significant one I’ve ever been involved in. Artistically first and foremost it is the most interesting way of making an album that’s ever happened to me. I start with the music because it’s important to start with the music for me. When you’re talking about political things or cultural things involving indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, for it to feel authentic the music has to feel right and solid from the beginning. After that to have the honour to spend time with the Yindjibarndi community with several trips back there has just been one of the greatest experiences of my life so far. Slowly from there the politics revealed themselves. I didn’t go got the Pilbara to write a political album, I didn’t go there waving a flag -I didn’t know what I was going to write about at first. Over a long time those things revealed themselves to me. The story of Ms Dhu happened just up the road, I knew about that before it reached mainstream media. In Melbourne that song was there and ready for us. We spoke to the family first. We wanted to make noise about that enquiry of late 2016 so moments like that happened because it was honest and it was there and it was real. What I’m getting at is that I was fortunate enough to be a part of an album that was a time and place that revealed itself to us. I was able to follow the music and through that I stand behind the messages in the song- it’s politics, it’s reverence and a celebration of country more than anything. I consider it an Australian album not an indigenous one exclusively obviously. I think too often in the media people say ‘this is an indigenous issue’ as if it’s their problem, it’s not it’s an Australian issue. It’s about who we are in this country and through music I’m able to express something that I’m deeply passionate about.

You’ve totally hit the nail on the head about the media labelling things as indigenous issues instead of Australian issues. You hear it all the time.

All the time! It’s crazy. Absolutely crazy. The thing is its difficult for a lot of people in cities to have the experience to spend time in communities and it changes you forever when you do that. You realise how many misunderstandings there are, how fraught institutional systems are around these issues, how much more compassion, celebration and joy we need to realise within ourselves culturally that there are opportunities we’re missing out on. There is so much we need to change, white Australia is missing out terribly. We are killing ourselves culturally, we need to be part of a huge paradigm shift.

[Interview by Leila Maulen]